Remembering Willie Jones (1931 – 2025)

His letters, stories about Japanese craftspeople, and our one conversation will stay with me for a very long time.

Who first had the idea of folding red-hot iron, and discovered that when the red-hot iron is mixed with burning charcoal the result will be carbonised steel? Was it because they lived next door to a volcano?

I met Willie Jones on the afternoon of the 172nd day of my walk around Japan, a day before I walked out of Sapporo, where he had been living for forty four years — over a quarter of the city’s history but less than half of his life. When I met him, the city glowed in the silver light of the last days of summer but a few days later a violent storm rolled in from the Sea of Japan and left the enormous volcano to the south dusted in the winter’s first snow. I walked from the subway to his house and found him in his study, a glorious view of the mountains and the city visible in the distance through half-drawn curtains. Through my field glasses, I could read the time on the digital clock halfway up the television tower that marks the eastern end of Ōdōri, the city’s tree-lined central thoroughfare.

Willie sat at his desk, bounded on all sides by ramparts of books, and for the next few hours we talked. He had moved to Japan in 1979 to teach at Hokkaido University, and he told me of those luminous days in the 1980s when this country was at the height of its economic power, the years when it was seriously believed that its economy would soon overtake the United States’s (the Japanese economy is now slightly smaller than that of California). Sapporo, Willie told me, was a grand, cosmopolitan city then, where you could go into the nicest shops and get the nicest things. As a child I read about these years in Michael Crichton’s Rising Sun — a novel from the perspective of American nationalism — and I type this from one of its many architectural remnants, an art studio that was built as a mayoral guesthouse in 1989, with a glorious view of the mountains and the city, a 15-minute walk from Willie’s study. He told me about his days as a runner. He was very tall, with long legs, and he had been very fast, and there was a picture of him in his 20s, sitting with all the trophies he’d won. I started running too late in life to be that fast but I thought I could imagine what he was talking about. To run fast on strong legs is pure ecstasy, transformative magic.

Soon after he came to Sapporo, where he would spend the rest of his life, Willie was commissioned by the editor of Hokkaido’s only English-language journal, Northern Lights, to write a series of articles about the craftsmen and craftswomen of Hokkaido. He would travel the island with the editor, Hisashi Urashima, and interview these people. His first piece was about a guy named Toshiharu Kinoshita, a young man whose choice of craft was odd even by Japanese standards: he decided, in the years when “the Japanese have found ways of incorporating digital clocks into electric shavers and video-taped menus into microwave ovens” — as Alan Booth, another Englishman who moved to Japan in the 1970s, wrote in 1985 — to become a swordsmith. On a late winter day, Willie and Mr. Urashima visited him, in “his tiny, newly-built house, just off the road, bounded on all sides by the snowy fields”, and Mr. Kinoshita unwrapped his creations.

When swordsmiths forge their lengths of steel they do it in the dark: they work only by the light of the red-hot metal and the light of the furnace. And since the forge is always sited a little distance from the house, the neighbours, seeing that gleam in the night in past times, may well have felt awe, have felt that this was no ordinary craft, that there was something semi-divine about those who practised it. We know that the secrets of smiths are metallurgical rather than metaphysical, and metallurgists can doubtless explain how half-molten metal when beaten may become a sword, but the blades that the smiths forged in the smithies of ancient Japan are superior to any sword that today’s smiths can produce, and nobody knows why. It is possible that magic came into it somewhere.

Willie would write me the most wonderful letters, in English that was not ordinary. He was intrigued by my journey, and I got the sense that if he weren’t confined to living in his 92-year-old body he would have come along with me as I walked on from his house all the way south-west to Kagoshima, then beyond. “I have thought of you when snow-storms have been battering the coasts facing the Sea of Japan, and have had the image of a tall man in a long black coat battling his lonely way like an arctic explorer through the drifts,” he wrote in one of his last letters.

Natalie, my wife, has observed over the years that people tend to live out the rest of their lives in the houses they move into in their 40s. I’m not sure when Willie moved into the house I visited him in, but he was 48 when he moved to Sapporo, and he died last Thursday at the age of 94. I never got to see him again and it’s purely my fault. He wrote me in early March, when he was released from the hospital and learned that I was coming back to Sapporo: “I hope very much that you will be able to visit me: I am sure that you will have wonders to speak of.” I kept putting off writing back, stupidly awestruck by his beautiful letters, and then I learned that he died, and now I don’t know his address.

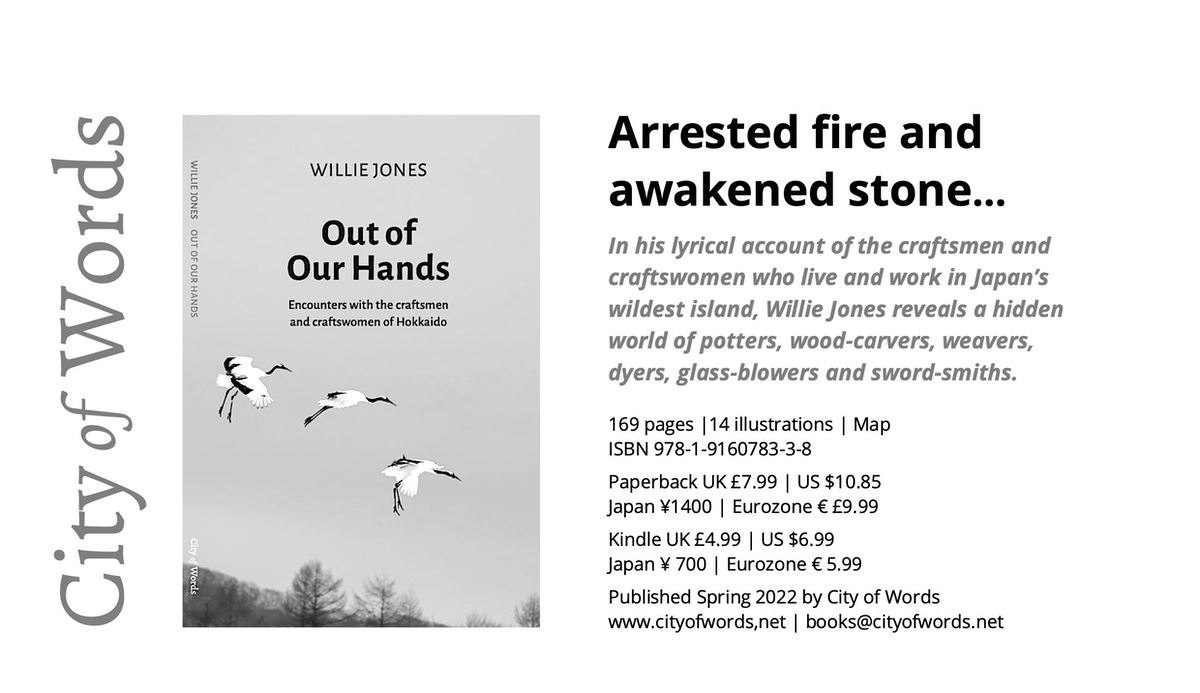

Natalie and I went to his wake. It was the fourth time in my life that I went to such an event and the first time in Japan. We took flowers, two for us and one for my friend, the writer and anthropologist John Ryle, one of Willie’s former students, who edited and published Out of Our Hands, a collection of Willie’s essays about the craftsmen and the craftswomen. The floral arrangements were extravagant and enormous, entire branches of birch covered in the golden-green leaves that have now unfurled around Sapporo after the six months of winter. There was a table set with Willie’s personal belongings: his comb, his wallet, a copy of the last issue of Northern Lights, which re-printed several of his essays. His walking stick hung from a clothes rack, next to his overcoat and his tweed cap. Someone had brought a tray of baked potato wedges, possibly the best Hokkaido convenience store snack, as I’m sure Willie also knew.

There were dozens of his Japanese students in attendance, and one of them, his back turned to us all, addressed the spirit of their teacher, the man who had taught him to write, in beautiful English. John Ryle told me once that it was Willie who had taught him how to use a semi-colon. I can’t use a semi-colon and I’m not a tall man in a long black coat battling his lonely way like an arctic explorer through the drifts, but I wanted to tell Willie of wonders nevertheless. About climbing the volcano Unzen, the hoarfrost-covered boulders near its summit like stone giants wading through a frozen sea, about the unsettling light at midnight over the river near my house in Estonia at the summer solstice, about the brown boobies that hunt flying fish like javelins in the steel blue waters of the East China Sea.

I never learned why he had wanted to be a swordsmith, or what daemon had driven him to take up the craft. I remained as much in the dark about this as the peasants who used to watch at a safe distance the glow of a swordsmith’s window against the blackness of the night.

I’m grateful to have known Willie. The blanket of sadness will, I hope, lift in time, and what I’ll remember is his letters, our one long conversation, his reading-chair that John Ryle once fell asleep in, the towers and ramparts and battlements of books that filled his study, his corridors, his bathroom, and, yes, the loo, too. I will remember, like his students, the glow of his words, and I think they will keep glowing for a very, very long time.

The quotes in this post are from the first essay in Willie Jones’s Out of Our Hands, an anthology of his Hokkaido pieces published in 2022 by City of Words. It is available for purchase on Amazon both in print and Kindle.