This private, impossible wonder

Confronting the impossibility of capturing my 9,000-kilometer journey through voice memos, memories, and notes. Can I make all this tangible? Perhaps what matters isn't why I walked but something else.

Two things I’ve learned since my previous post:

- A chicken dinner from May 2017 made me realize the utter impossibility of what I’m trying to do here.

- Why is a really dumb thing to ask about anything worth doing.

Also, a third: March in Sapporo is a riot:

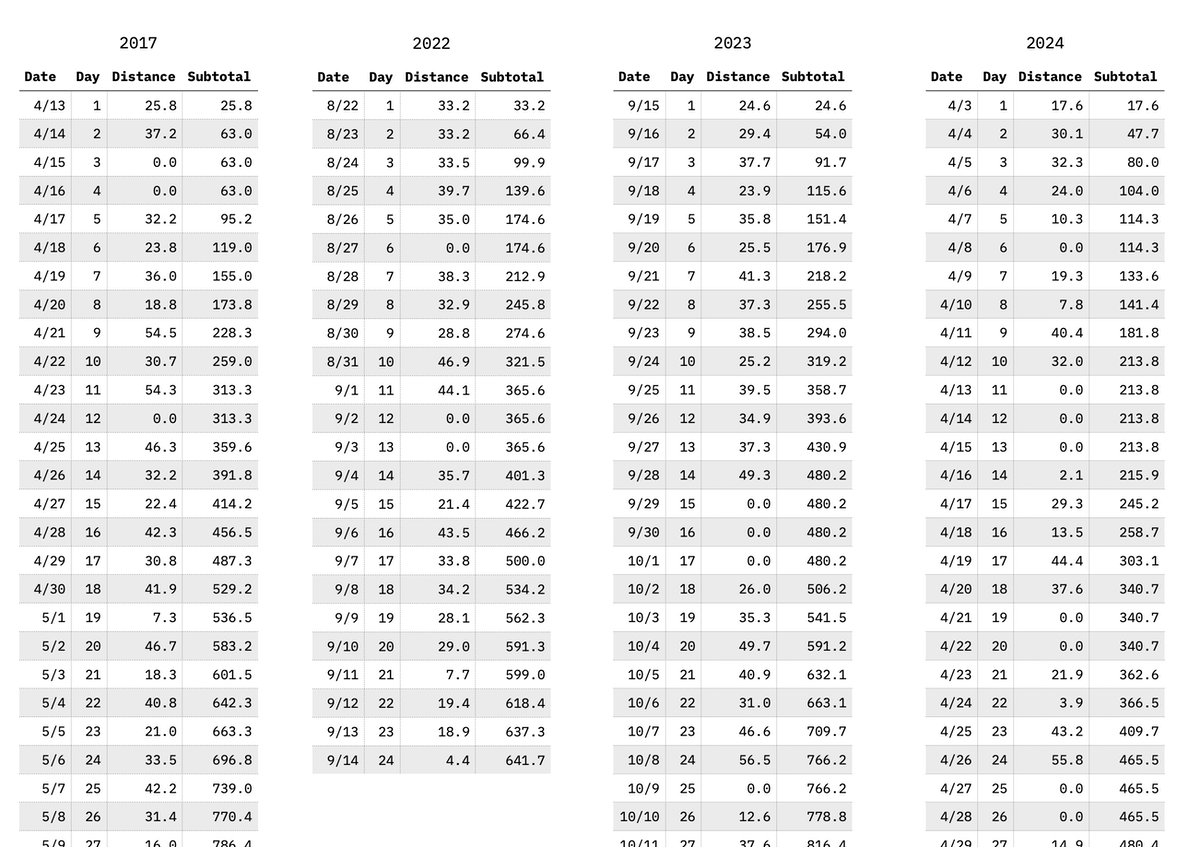

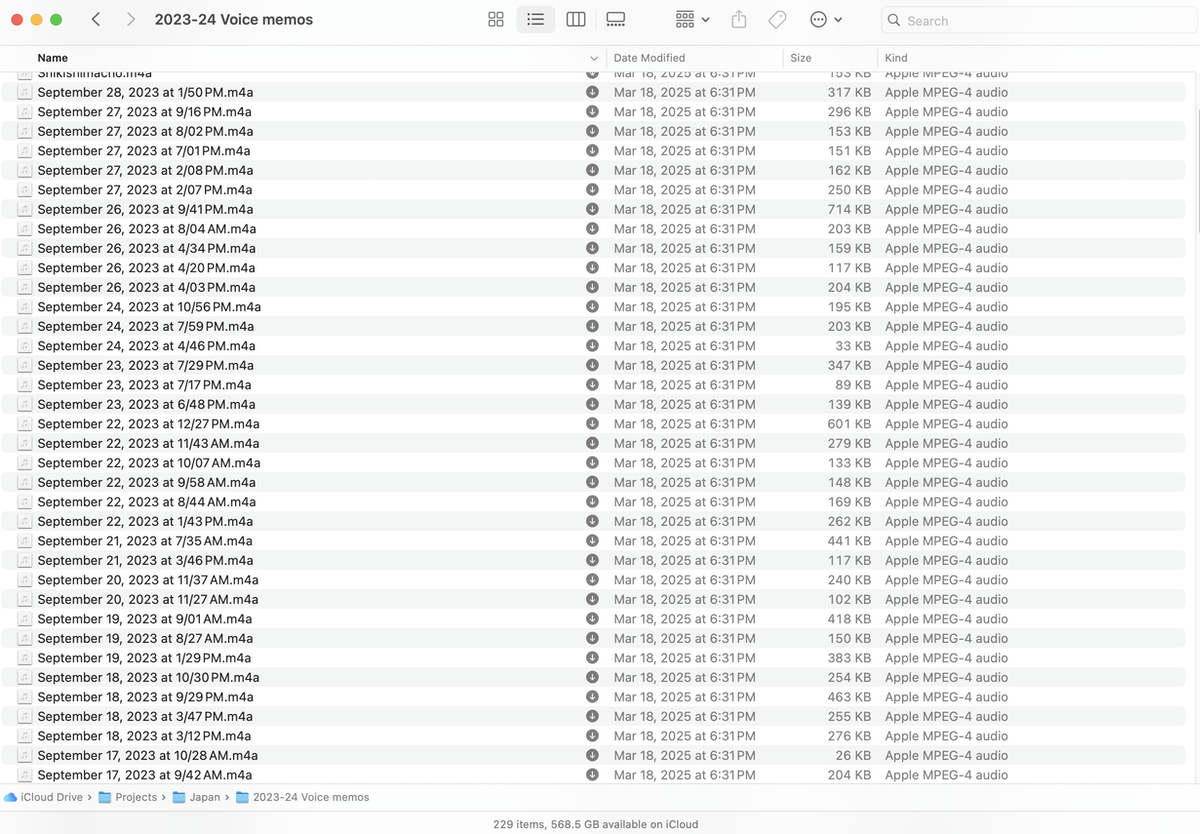

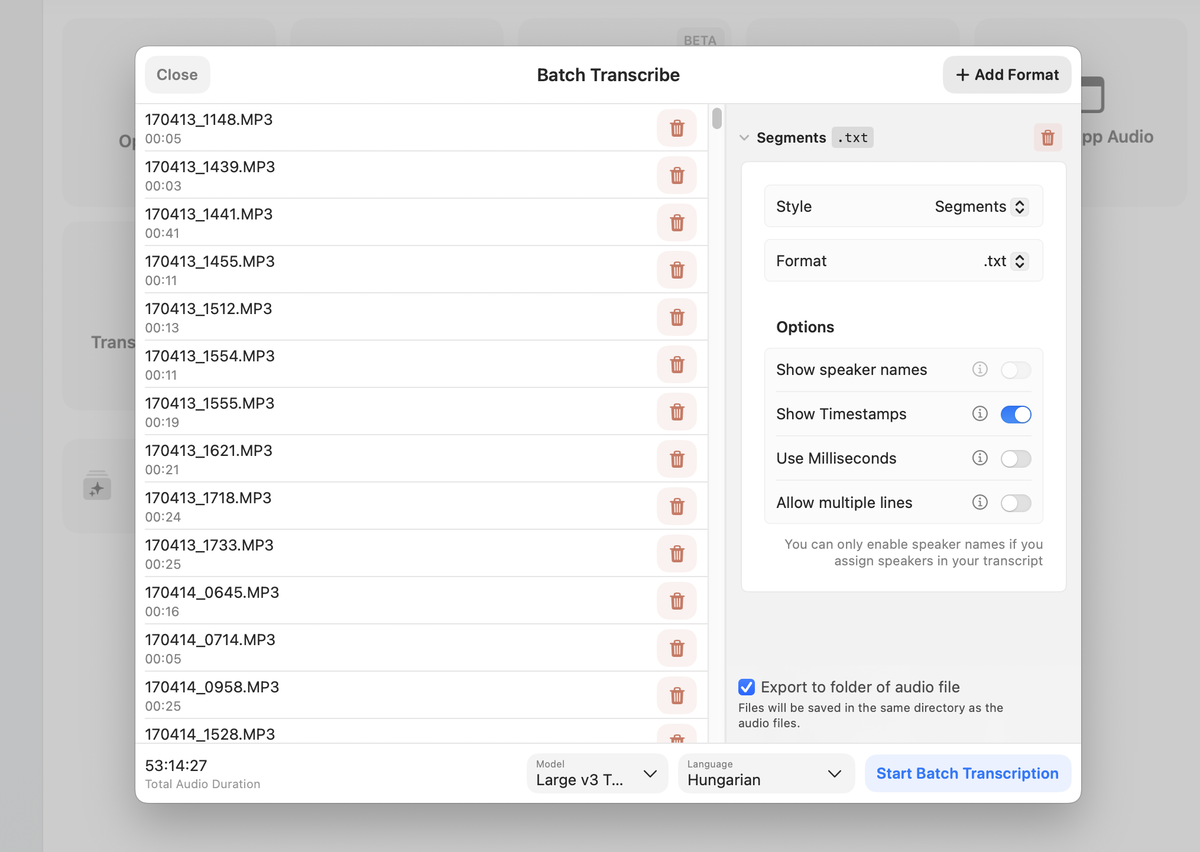

Before I write about #1 and #2, I’d like to invite you to observe the glamour of data reduction. Mountainsides, hot springs, weird characters in the woods, they all turn into stuff on a computer screen.

Like this:

And this:

Also, this:

Embarrassingly low-key in an art studio where one of my neighbors is a guy named Lou, a Sephardi from Madeira living in the Maya Highlands, who makes a sculpture each day. They keep piling up on his workbench, mad-looking animal spirits, and I sigh and long for something tangible.

05:13:34-05:13:35 thud

When I left Kagoshima on April 13, 2017, my idea was that I would be a very diligent observer and record everything of note. Then, presumably, do something with those notes, because that’s what travel writers (!) do. The technical problem was how to record. My hands are occupied when I walk, one holding my walking-stick — step-step-step-stepclick-step-step-step-stepclick — the other checking the map, operating the camera, surreptitiously picking fruit, et cetera, and both are generally too grimy to type reliably on a screen. The only sane choice was to put aside my general dislike of voice interfaces and clip a little Sony voice recorder to my rucksack:

By the end of this first part of my journey, I had over a thousand recordings, more than 20 hours in total. I kept shunting them from computer to computer for years. I can’t stand the sound of my voice on a recording, and even if I did, manually transcribing a thousand notes was out of the question. An anthropologist friend suggested that this is what student gigs are for, and that I should just find someone at a university and pay them to do it. I never got around to it, and I’m really glad I didn’t because the enchanting wave of technology that is now upon us caught up with my problem at last. The solution to all my years of hand- and ear-wringing turned out to be selecting the files, dragging them into OpenAI’s Whisper speech recognition model, and watching in amazement as the machines transcribed the whole lot, in perfectly punctuated Hungarian, in less than an hour. I ended up with a large folder of text files. I poked around them at random. They were a little messy but perfectly readable. They brought back a lot of memories.

Then I noticed something odd with some of the files. About a dozen or so were absolutely enormous. Most of my recordings are 15 seconds, 30 seconds, rarely longer than two minutes, small files, but these big ones ran on for hours: the longest for half a day.

What must have happened was I turned on the recorder and didn’t turn it off and it just kept running…and running…and recording. At least two of these giant recordings captured very interesting parts of the journey. One is a four-hour session of my brother Gabor and I walking some 20 kilometers out of Hakodate, on our first day together across Hokkaido. We hadn’t seen each other in four months. We talk non-stop, about things that still occupy my mind.

The other is on Awaji, that large-ish small island wedged between Shikoku and the Japanese mainland, at the end of a day when I walked 47 kilometers in the hot sun, my stomach shot from either an unripe loquat or a too-ripe piece of fish. I hit REC at around 8 PM, meeting up with my new friend Stephen, a Kiwi bee-keeper I’d met the evening before at a bathhouse. He buys me a plate of fried chicken, then we get some beers and Stephen shows me a nice seaside park where I can put up camp. We sit there and talk until the wee hours. Five hours, ten minutes, and seven seconds in, Stephen signs off:

05:10:07-05:10:08

Thank you man. Bye.05:10:10-05:10:10

Good night.05:11:28-05:11:31

Thank you.05:13:34-05:13:35

thud05:15:21-05:15:26

I'm going to go.05:16:01-05:16:04

thud05:16:25-05:16:28

So, let's go.

The thud is Stephen kickstarting his motorcycle. Some time later, I can hear the sound of my battery-powered mattress pump whirring away (if you recall the very last scene of Eric Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, you have my endorsement for a laugh). Then my breathing for hours. I wake up around 8 AM, and I guess I remember to turn off the recorder or maybe the battery just goes.

Here is an entire half-day of my 298-day journey accidentally captured in audio. I remember next to nothing of it. I remember the vibe (it was good). I remember small details. I remember Stephen telling me about the ability of the indigenous Japanese honeybees to surround the giant Japanese hornets that attack their hives in little furry bee-balls and cook those songbird-sized vespi-copters to death. I remember how he told me about the great Kobe earthquake of 1995, the one that pushed the pylons of the under-construction Akashi-Kaikyō Bridge apart so that they now span 1,991 meters instead of 1,990, and how the next evening I would watch shimmering green moths flutter in the night and watch this ludicrous structure above the sea, a floating mirage the size of a geographical feature instead of a building. But most of it I don’t remember, and most days are barely recorded in such exacting detail, and how am I going to write about EVVVVVERYTHING if nothing is mostly what I remember.

Contributions from all the possible paths

One of the books I read this past winter was Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Between the Woods and the Water, about the middle part of his walk across Europe in 1934. I read it in fits and starts, mostly at night (which is not saying much in the Estonian winter). It turned out to be a very apt way to read this wonderful book: written decades after the walk that it’s about, and published in 1986 — the same year as Alan Booth’s The Roads to Sata, which was one of the books that inspired my walk around Japan.

Between the Woods and the Water may be contemporaneous with Booth’s book but it feels like it’s from another century: one is about 1934 Hungary and Romania (Rumania!), the other about 1977 Japan, and Leigh Fermor and Booth couldn’t be more different in style. He writes about a Central Europe suspended in time, its feudal past still tangible but fading by the day, a hyper-local world of kastélys and dusty ways and sweep-wells that’s nevertheless connected with other worlds in space and time, a Central Europe that is now simply gone. On horseback, he passes near the house of my then-eight-year-old grandmother. Instead of a voice recorder (we’re in 1934), he keeps a diary — in a “thick green manuscript book I bought in Bratislava” — which he leaves by mistake at a girlfriend’s country house in Moldavia, then gets it back decades later. And he writes his book in the 1970s based on that, and his teen-age memories. It’s a splendid book, vivid and alive, and it shimmers with boundless wonder about this world that, for me, slipped from living memory with the passing of my grandmother, eighty eight years after Leigh Fermor rode his horse near the Swabian farming town where she was born and lived all her life and is buried.

Last week I wrote, with considerable hubris, that “the wiggle of the path that I walked around Japan should be tangible to almost everyone” but now I’m not so sure. Every journey of any length is basically impossible to make tangible, and going on foot only makes things worse. One of the mysterious effects of a long walk is that one enters a state of mind in which patterns are created all the time — maybe a side effect of trying to process all that stuff that’s constantly happening? — and these patterns tend to be very beautiful and often verge on the numinous. How can one disentangle oneself from these mirages, these paths that travel to the far reaches of the universe? How can one, building on notes and memories under a constant state of assault from seductively beautiful but suspiciously random patterns, arrive at the truth? How can one stand fully outside oneself?

All of which leads, in a disgustingly metaphysical way — feh! — to this paragraph from Leonard Mlodinow’s Feynman’s Rainbow, a slim, charming book about a young physicist crossing paths with a half-real, half-mythical Richard Feynman in 1980s California:

In Feynman’s approach, to find the probability that an electron that started in a given initial state would end up in some particular final state you add, using certain rules, contributions from all the possible paths, or histories, of the electron that could take it from the initial state to the final one. To Feynman, this was what distinguished the quantum world from the everyday, or classical, world. In classical theories a particle followed a definite path, just as objects seem to in our everyday world. The strange quantum world arises because you have to take into account extra paths. For large objects, the way you add up the paths makes only one of these important, the familiar classical path, so you don’t notice any quantum effects. But for subatomic particles, such as the electron, you cannot ignore paths in which the electron travels to the far reaches of the universe, or zigzags back and forth in time. The quantum electron shoots around the universe in a cosmic dance, from present to future to past, from here to everywhere in the universe, and back. In following these paths, it ignores the orthodox rules of motion and acts as if nature had let go of the controls. As Feynman put it, even “the temporal order of events…is irrelevant.” Yet somehow, like the music of instruments in harmony, all these paths, added together, add up to the final quantum state that the experimenter observes.

As wary as I am of using science as metaphor, I can’t help but think that Mlodinow’s description of Feynman’s visualization of quantum mechanics is a wonderfully apt analogy for what I’m trying to do: to make tangible the private, impossible wonder of a long walk, with all these extra paths and zigzags back and forth in space and time. We cook with what we have. Thick green manuscript books, voice recordings, teen-age memories, beachside conversations, all maddeningly incomplete. What matters, perhaps, is this: are the instruments in harmony? Can you hear the music?

Why isn’t the pertinent question: it’s simply the sum of all paths added together.

In my next installment, I’m going to write about how, and, yeah, also about spring days in Kagoshima.