A half-assedly thought-out pictorial semi-vision thing

A walking journey of 9,000 kilometers around Japan, spanning 7 years and 18 islands. Follow along as I process the raw data of this walk to determine if this adventure deserves to become a book.

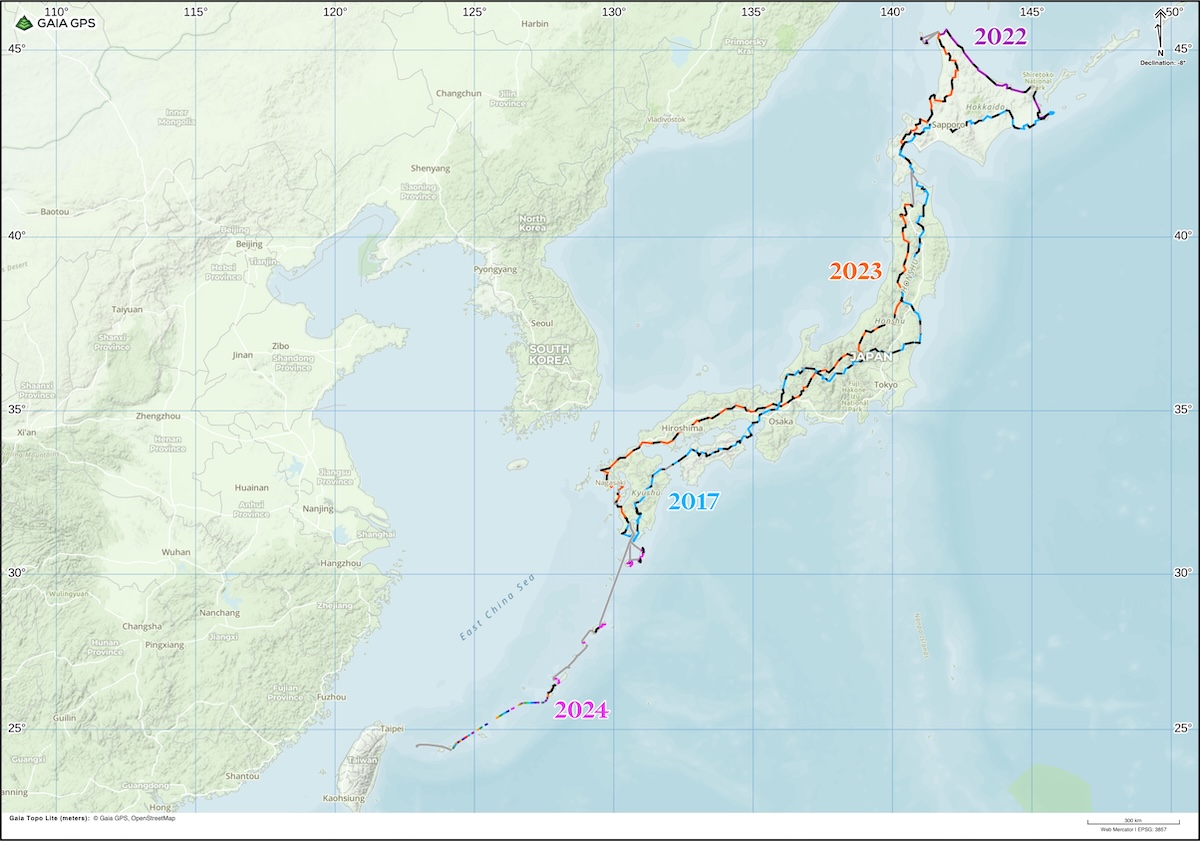

On the morning of April 13, 2017, I walked out of my friend Sahar Ghavidel’s house in the southern Japanese city of Kagoshima, pushed my bike a few blocks down the street and left it in the parking lot of a dormitory for another friend, ate a breakfast sized for a wrestler at the cafeteria of Kagoshima University, then walked out of the city with a rucksack on my back, walked on, and didn’t stop. By the time I returned to the same spot, on the early evening of January 6, 2024, Sahar had moved to another house, then to Tehran, then to eastern Iran, then back to Tehran, then back to Japan, and when I called her from below what had been her living room window, giggling, she picked up the phone on her way to St. John’s, Canada. A couple of months later I left the Japanese mainland and walked across some of the islands to the south until I reached the country’s westernmost end, Cape Irizaki on Yonaguni Island, on the morning of May 1, 2024. By then, I had walked 9,000 kilometers around, and out of, Japan.

The journey was in four separate parts, in 2017, 2022, 2023, and 2024, during which I touched the Japanese mainland’s southern-, eastern-, northern-, and westernmost points, along with its geographical center, while walking around 9,000 kilometers across 18 of the country’s 14,125 islands and climbing or traversing 18 of its high mountains. Apart from the ferries I took between the islands, three short car rides in places where it was forbidden to walk (a toll road, a toll bridge, and a nuclear exclusion zone), and a flight from Okinawa to Ishigaki on the penultimate evening of my journey, I walked every step of the way (9,000 kilometers is the distance I walked, I didn’t add up the ferry rides and such).

Data Reduction 9K, this blog/newsletter/mailing list, is going to be about me trying to figure out if this whole thing was interesting enough for a book. For the next three months, I am graciously hosted for this project by Tenjinyama Art Studio in Sapporo, Japan, where I type this while listening to the snow squalls blowing in off the Sea of Japan.

Why

“When I am asked, ‘Why did you go to Ethiopia?’ I find it impossible to give a short, clear answer,” begins Dervla Murphy’s In Ethiopia with a Mule, the account of her 1966 trek across Ethiopia with a pack-mule named Jock. “I’m not good at explaining why I walked across Afghanistan,” begins Rory Stewart’s The Places in Between, the account of his 2002 trek across Afghanistan with a war dog named Babur. I had neither a pack-mule nor a war dog to accompany me, and most of the time I walked on my own. But there were days and weeks when I would be joined by kith and kin, and there was one person who joined me for some time on all four parts of the journey: my brother, Gabor.

Gabor works as a radio astronomer, which is a fairly obscure field of science, but there’s a good chance you’re very familiar with a particular measurement from radio astronomy’s early years, which is shown on the cover of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures — an album released on Gabor’s future birthday, eight years before he was born.

The image shows what’s called a ridgeline plot of the radio emissions given out by the pulsar CP 1919, a rotating neutron star. It’s an excellent illustration of the fundamental abstraction of radio astronomy. Humans, even radio astronomers, don’t have receptors for radio waves. If you choose to study nature through them, you’re going to spend the majority of your working hours looking down at computers instead of up at the sky. Or, if you don’t know what you’re doing, looking up at the computers, like me (in green), when I visited the control room of the VERA Iriki radio telescope in 2013 with Gabor (in blue). It’s up in the hills above Kagoshima, the city where I would begin my walk four years later, and where Gabor was living at the time.

Data reduction, the scientific term I looted from Gabor’s work vocabulary to misuse as the name of this blog, describes the process of what you do with the information collected by the radio telescopes and the computers, turning what’s real but very abstract into something tangible, like the ridgeline plot that shows the emissions of CP 1919, or like Murphy’s and Stewart’s books about their journeys across Ethiopia and Afghanistan. In my case, it’s going to be the act of taking the raw data of my 9,000-kilometer walk — the voice memos, the maps, the notebooks, the photos, the memories — and attempt to reduce it into what I hope will be an answer to my question: was this interesting enough for a book? If the answer turns out to be yes, I’m going to write a book about it. If not, then what I’ll have written about it will be this blog only (and the diaries I kept in 2017 and 2022, on the first two parts of the journey).

The wiggle of a path

That the act of walking can turn into something no less abstract than the radio waves emitted by a neutron star simply through its scale is a very strange phenomenon. Humans may have no receptors for radio waves but walking is among our simplest skills. It takes years of training and a keen mind to be able to make sense of radio astronomy data but any able-bodied person could go out and walk 9,000 kilometers. Yet the number of people who have done so is likely fewer than the number of people who can interpret radio astronomy data, let alone who could do so, which would be a number in the billions. For reasons I don’t fully understand, the length of a walking journey turns this most mundane act into something ludicrous and somewhat inhuman that even excellent writers apparently struggle to explain.

Perhaps it has to do with the quirks of our imagination. We try to imagine walking 9,000 kilometers as a single, enormous act instead of as a succession of millions of tiny acts: footsteps. A walk to the corner store or your local café are easy and comforting to imagine, journeys on a human scale, but if you take the wiggle of a path through and around Japan, straighten it out, and draw it on a map, it will stretch into something alien and monstrous, extending across Eurasia from, say, Riga to Saigon, one end dangling into the Baltic Sea, the other into the South China Sea, a journey for jet airplanes, not humans. And while it would be extremely difficult to walk across Eurasia in a straight line, it is within the capabilities of every able-bodied human to walk 9,000 kilometers. I know because I both did and did not do such a thing. I just walked out of my friend’s house in Kagoshima, turned a corner, then another corner, then climbed a hill, and walked on. The magic begins when you don’t stop. Kilometers are just a way of keeping score.

Jiggle-jiggle-jiggle

There’s another endeavor that’s concerned with turning what’s real but abstract into something tangible, a field of science as complex as walking is simple: theoretical physics. Here is how Richard Feynman, one of its greatest practitioners, described his explorations of the interaction between light (photons) and matter (electrons) in the late 1940s, as recounted in James Gleick’s biography Genius:

What I am really trying to do is bring birth to clarity, which is really a half-assedly thought-out pictorial semi-vision thing. I would see the jiggle-jiggle-jiggle or the wiggle of the path. […] It’s all visual. It’s hard to explain.

The wiggle of the path of a probabilistic electron is only visible to someone with Feynman’s genius, and perhaps a few others, but the wiggle of the path that I walked around Japan should be tangible to almost everyone. In the next three months, on this half-assedly thought-out blog, I’m going to try and see if I can make it so. It might be hard to explain but it’s mostly visual. I hope you’ll find it worthwhile to jiggle-jiggle-jiggle along.

Next up: a beautiful spring day in Kagoshima, serious doubts, a volcano at the end of Japan, the road to Sata, in the company of deer, the end of the beginning.

See you next week!

Peter